Americas Hero Again His Victory the Comeback That America Needed

| Appointment | June xix, 1936 and June 22, 1938 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Championship(due south) on the line | Earth Heavyweight Title (2nd fight) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tale of the tape | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling (or Max Schmeling vs. Joe Louis) refers to 2 carve up fights between the men which are amongst boxing'due south most talked-about bouts. Schmeling took the offset match in 1936 by a knockout in round 12 but Louis won the 2nd bout in 1938 with a knockout in the first round. The two fights came to embody the broader political and social disharmonize of the time. As the well-nigh significant African American athlete of his historic period and the most successful black fighter since Jack Johnson, Louis was a focal betoken for African American pride in the 1930s. Moreover, equally a contest between representatives of the United States and Nazi Deutschland during the 1930s, the fights came to symbolize the struggle betwixt democracy and Nazism. Louis' performance in the bouts made him i of the first true African-American national heroes in the The states.

Prelude to commencement fight [edit]

Joe Louis was born in Alabama, but lived much of his early years in Detroit. Every bit a successful African American professional in the northern part of the country, Louis was seen by many other Americans as a symbol of the liberated black human. Since becoming a professional person heavyweight, Louis amassed a record of 24–0 and was considered invincible heading into his first bout with Schmeling in 1936.[1] Louis' celebrity was especially of import for African Americans of the era, who were not but suffering economically along with the rest of the country but also were the targets of meaning racially motivated violence, particularly in Southern states past members of the Ku Klux Klan. By the time of the Louis-Schmeling match, Schmeling was idea of as the last stepping stone to Louis' eventual championship bid.

Max Schmeling, on the other hand, was born in Germany, and he had become the first world heavyweight champion to win the title past disqualification in 1930, against Jack Sharkey, another American. One year subsequently, Schmeling retained his title past a Round 15 knockout against William Stribling. Later Schmeling lost the title in a rematch with Sharkey by a very controversial decision in 1932. As a result, Schmeling was well known to American boxing fans and was yet considered the No. ii contender for James Braddock'southward heavyweight title in 1936. Nevertheless, many boxing fans considered Schmeling, xxx years quondam by the time of his get-go match with Louis, to be on the turn down and non a serious claiming for the Chocolate-brown Bomber.[one]

Perhaps, equally a result, Louis took training for the Schmeling fight none too seriously. Louis' training retreat was at Lakewood, New Bailiwick of jersey, where Louis was introduced to the game of golf game – later to become a lifelong passion. Louis spent significant fourth dimension on the golf game course rather than training.[2] [three] Conversely, Schmeling prepared intently for the tour. Schmeling had thoroughly studied Louis'south style, and believed he had institute a weakness:[4] Louis'due south habit of dropping his left mitt low later a jab.[five]

Although the political attribute of the first Louis-Schmeling bout would later exist dwarfed by the crucible of the later 1938 rematch, brewing political sentiment would inevitably attach itself to the fight. Adolf Hitler had become chancellor of Frg three years previously and, although the U.s. and Federal republic of germany were not withal political or armed services enemies, there was some tension building amidst the two countries every bit the Nazi Party began asserting its pro-Aryan, anti-Jewish ideology. Schmeling'southward Jewish manager, Joe Jacobs, prepare Schmeling'due south grooming at a Jewish resort in the Catskills, hoping it would help mollify Jewish fight fans.[6]

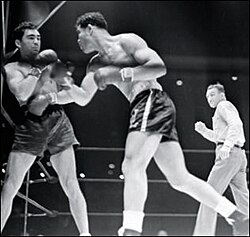

Commencement fight [edit]

Louis vs. Schmeling, 1936

The get-go fight between Louis and Schmeling took place on June 19, 1936, at the famous Yankee Stadium in Bronx, New York. The referee was the legendary Arthur Donovan, and the stadium'southward seats were sold out. The bout was scheduled for fifteen rounds. 57 1000000 people listened on their radios.

Schmeling's study of Louis' manner led him to openly say, in days earlier the fight, that he had found the central to victory; fans thought that he was simply trying to raise interest in the fight. Notwithstanding, battle fans still wanted to see the rise star confronting the famed old world champion.

Schmeling spent the first 3 rounds using his jab while sneaking his right cross behind his jab. Louis was stunned by his rival'southward manner. In the quaternary round, a snapping right landed on Louis' chin, and Louis was sent to the canvas for the showtime fourth dimension in his twenty-eight professional person fights. Every bit the fight progressed, stunned fans and critics alike watched Schmeling go on to use this way effectively, and Louis had no thought how to solve the puzzle.

As rounds went by, Louis suffered various injuries, including i to the eye. Louis remained busy, trying to land a punch that would requite him a knockout victory, but, with eyesight trouble and Schmeling's jab constantly in his face, this proved incommunicable.

Past circular twelve, Schmeling was far ahead on the judges' scorecards. Finally, he landed a right to Louis' trunk, followed by some other correct mitt, this one to the jaw. Louis fell near his corner and was counted out by Donovan. This was Louis' only knockout defeat during his commencement run: the simply other knockout happened when Rocky Marciano knocked Louis out fifteen years later. By then, Louis was considered a faded champion and Marciano a rising star.

Among the attendees at Louis' defeat was Langston Hughes, a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance and noted literary figure.[seven] Hughes described the national reaction to Louis' defeat in these terms:

I walked downwards Seventh Avenue and saw grown men weeping like children, and women sitting in the curbs with their heads in their easily. All across the country that night when the news came that Joe was knocked out, people cried.[7]

Conversely, the German reaction to the outcome was jubilant. Hitler contacted Schmeling's wife, sending her flowers and a bulletin: "For the wonderful victory of your married man, our greatest High german boxer, I must congratulate you with all my heart."[half dozen] Schmeling dutifully reciprocated with nationalistic comments for the German press, telling a German reporter after the fight:

At this moment I take to tell Germany, I take to report to the Fuehrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight; that the Fuehrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the force to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Frg'southward colors.[6]

Prelude to 2d fight [edit]

The weigh-in for Louis vs. Schmeling, 1938

Later on his victory over Louis, Schmeling negotiated for a title bout with world heavyweight champion James J. Braddock. But the talks fell through – partially considering of the more than lucrative potential of Louis-Braddock matchup, and partially because of the possibility that, in the event of a Schmeling victory, Nazi regime would not allow subsequent title challenges by American opponents.[8] Instead, Louis fought Braddock on June 22, 1937, knocking him out in eight rounds in Chicago. Louis, however, publicly appear after the fight that he refused to recognize himself as world champion until he fought Schmeling again.

The United States economy had long been suffering from the Great Depression when these ii combatants had their 2 fights. The economical problem affected the The states throughout the 1930s, and many Americans sought inspiration in the world of sports.

Compounding the economic instability was a heated political conflict between Nazi Federal republic of germany and the The states. Past the time of the Louis–Schmeling rematch in 1938, Nazi Germany had taken over Austria in the Anschluss, heightening tensions betwixt Germany and the other Western powers, and generating much anti-German propaganda in the American media.[9] The High german authorities generated an onslaught of racially charged propaganda of its own; much of it created by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels based on Schmeling'southward success in the boxing earth.[1]

Schmeling did not bask existence the focus of such propaganda. He was not a member of the Nazi Party and – although proud of his German language nationality – denied the Nazi claims of racial superiority: "I am a fighter, not a politico. I am no superman in any way."[ten] Schmeling kept his Jewish manager, Joe Jacobs, despite meaning pressure level,[11] and, in a dangerous political run a risk, refused the "Dagger of Award" award offered by Adolf Hitler.[12] [13] In fact, Schmeling had been urged by his friend and legendary ex-champion Jack Dempsey to defect and declare American citizenship.[10] Schmeling never did revoke his High german citizenship, however. Schmeling was quoted saying, "One time a German, always a German language."[14]

Nevertheless, the Nazi government exploited Schmeling in its propaganda efforts and took careful steps to at least ensure Schmeling'south nominal compliance. Schmeling's wife and mother were kept from traveling with him to avoid the chances of defection.[10]

Schmeling's entourage also included an official Nazi Party publicist. The publicist not only controlled any possible contrarian remarks past Schmeling, but also issued statements that a black human could not defeat Schmeling, and that Schmeling'south handbag from the fight would be used to build more German tanks. Hitler himself lifted the nationwide 3:00 a.m. curfew and so that cafés and bars could bear the broadcast for their patrons.[i] As a result, the perception of the American public had turned decidedly confronting Schmeling between 1936 and 1938. Schmeling was picketed at his hotel room, received a tremendous corporeality of hate mail service, and was assaulted with cigarette butts and other detritus as he approached the ring.[1] [xv] [16]

A few weeks earlier the rematch, Louis visited President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the White House. The New York Times quoted Roosevelt as telling the fighter, "Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Frg."[1] In his 1976 biography, Louis wrote, "I knew I had to get Schmeling good. I had my own personal reasons and the whole damned country was depending on me."[half dozen] This time, Louis took training for the tour seriously, giving upwards golf and women throughout his training.[17] Joe Louis said to a friend before the fight, "Yep, I'one thousand scared. I'thou scared I might kill Schmeling."[18]

A few days before the fight, the New York State Able-bodied Commission had ruled that Joe Jacobs, Schmeling's manager, was ineligible to work in the German's corner, or be in the locker room, as penalization for a previous public relations infraction involving fighter "Two-Ton" Tony Galento.[15] In addition, Schmeling'due south normal cornerman, Doc Casey, declined to work with Schmeling, fearing bad publicity.[nineteen] As a result, Schmeling sat anxiously in the locker room before the bout; in contrast, Louis took a ii-60 minutes nap.[20]

2nd fight [edit]

Louis vs. Schmeling, 1938

The Louis-Schmeling rematch came on June 22, 1938 – one year from the day Louis had won the world Heavyweight title. The fighters met once once more in a sold-out Yankee Stadium in New York City. Amongst the more than lxx,000 fans in attendance were Clark Gable, Douglas Fairbanks, Gary Cooper, Gregory Peck, and J. Edgar Hoover.[1] The fight drew gate receipts of $one,015,012 (equivalent to $19.v one thousand thousand in 2021).[1] lxx million listened on radio in the U.S., and over 100 million around the earth.

Schmeling came out of his corner trying to apply the aforementioned style that got him the victory in their first fight, with a directly-standing posture and his left hand prepared to begin jabbing.

Louis' strategy, however, had been to get the fight over early on. Before the fight, he mentioned to his trainer Jack "Chappie" Blackburn that he would devote all his energy to the first three rounds,[19] and even told sportswriter Jimmy Cannon that he predicted a knockout in i.[17] Afterwards only a few seconds of feinting, Louis unleashed a tireless barrage on Schmeling.[21] Referee Arthur Donovan stopped action for the kickoff time but over one infinitesimal and a half into the fight later on Louis connected on five left hooks and a trunk blow to Schmeling's lower left which had him audibly crying in pain.[21] Afterwards sending Louis briefly to his corner, Donovan quickly resumed activeness, afterward which Louis went on the assault again, immediately felling the German with a right claw to the face. Schmeling went down this time, arising on the count of three.[22]

Louis and so resumed his barrage, this fourth dimension focusing on Schmeling's caput. Subsequently connecting on three make clean shots to Schmeling'due south jaw, the German fell to the sail again, arising at the count of ii.[23] With Schmeling having few defenses left at this indicate, Louis connected at will, sending Schmeling to the sail for the third time in brusk order, this time well-nigh the ring's center.[23] Schmeling's cornerman Max Machon threw a towel in the ring – although, under New York country rules, this did not end the fight.[23] Machon was therefore forced to enter the band at the count of viii, at which point Donovan had already declared the fight over.[24] Louis was the winner and world Heavyweight champion, by a technical knockout, 2 minutes and iv seconds into the get-go round. In all, Louis had thrown 41 punches in the fight, 31 of which landed solidly.[21] Schmeling, past contrast, had been able to throw only two punches.[24] Soundly defeated, Schmeling had to be admitted to Polyclinic Hospital for 10 days. During his stay, it was discovered that Louis had cracked several vertebrae in Schmeling's dorsum.[i] [23]

Schmeling and his handlers complained afterward the bout that Louis' initial volley had included an illegal kidney punch, and even refused Louis' visitation at the hospital.[23] The claim resounded hollowly in the media, even so, and they eventually chose non to file a formal complaint.[23]

Aftermath [edit]

The fight had racial equally well equally political undertones. Much of black America pinned its hopes on the consequence of this Joe Louis fight and his other matches, seeing Louis' success every bit a vehicle for advancing the crusade of African Americans everywhere. Poet and author Maya Angelou, among others, recounted her recollection of the first Louis-Schmeling fight. She had listened to the fight over the radio in her uncle's state store in rural Arkansas. While Louis was on the ropes,

My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, withal another black man hanging on a tree . ... this might exist the end of the world. If Joe lost nosotros were back in slavery and beyond help. It would all be truthful, the accusations that we were lower types of homo beings. Just a little higher than the apes ...[25]

Conversely, when Louis won the rematch fight, emotions were unbounded:

Champion of the world. A Blackness boy. Some Black mother's son. He was the strongest human in the world. People drank Coca-Cola like ambrosia and ate processed bars like Christmas.[26]

In his autobiography, Schmeling himself confirmed the public'due south reaction to the event, recounting his ambulance ride to the hospital afterward: "Equally we drove through Harlem, there were noisy, dancing crowds. Bands had left the nightclubs and bars and were playing and dancing on the sidewalks and streets. The whole expanse was filled with celebration, noise, and saxophones, continuously punctuated by the calling of Joe Louis' name."[ane]

Reaction in the mainstream American press, while positive toward Louis, reflected the implicit racism in the United States at the time. Lewis F. Atchison of The Washington Postal service began his story: "Joe Louis, the lethargic, craven-eating young colored boy, reverted to his dreaded part of the 'brown bomber' this night"; Henry McLemore of the United Press chosen Louis "a jungle human being, completely primitive as any savage, out to destroy the thing he hates."[27]

The day later on the fight, blues musician Pecker Gaither recorded one of his most famous songs, "Champ Joe Louis," a song praising the champ in his defeat of Max Schmeling.[28]

Although Schmeling rebounded professionally from the loss to Louis (winning the European Heavyweight Title in 1939 by knocking out Adolf Heuser in the 1st round), the Nazi authorities would cease promoting him as a national hero. Schmeling and Nazi authorities grew further in opposition over time. During the Kristallnacht of November 1938, Schmeling provided sanctuary for two immature Jewish boys to safeguard them from the Gestapo.[11] Conversely, as a mode of punishing Schmeling for his increasingly public resistance, Hitler drafted Schmeling into paratrooper duty in the German language Luftwaffe. Later brief military service and a comeback attempt in 1947–48, Schmeling retired from professional boxing. He would go on to invest his earnings in diverse post-War businesses. His resistance to the Nazi party elevated his status in one case once more to that of a hero in post-state of war Federal republic of germany.

Louis and Schmeling, 1971. The former rivals became close friends in afterwards life

Louis went on to become a major celebrity in the United States and is considered the first true African American national hero.[29] When other prominent blacks questioned whether African Americans should serve confronting the Centrality nations in the segregated U.Due south. Armed services, Louis disagreed, maxim, "At that place are a lot of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain't gonna gear up them." He would continue and serve the United States Regular army during World War II, only he did not engage in battle while the war was going on. He mostly visited soldiers in Europe to provide them with motivational speeches and with boxing exhibitions. He kept defending the world heavyweight title until 1949, making twenty-five consecutive title defenses – yet, a earth record among all weight divisions for men's boxing (Regina Halmich, a woman boxer, made 29 defenses of her Women'due south International Battle Federation world Flyweight championship).[thirty]

Louis' finances evaporated later in life, and he became involved in the utilize of illicit drugs.

Louis and Schmeling developed a friendship outside the ring, which endured until Louis' death on Apr 12, 1981. Their rivalry and friendship was the focus of the 1978 Tv set motion-picture show Ring of Passion.[31] Louis got a job as a greeter at the Caesars Palace hotel in Las Vegas, and Schmeling flew to visit him every year. Louis was reportedly then in demand of money, but too damaged to box anymore, so the sometime champion took up professional person wrestling to make ends see.[32] Schmeling reportedly as well sent Louis coin in Louis' later years and covered a part of the costs of Louis' funeral, at which he was a pallbearer. Schmeling died 24 years later on February 2, 2005 at the historic period of 99. He was ranked 55 on The Ring'due south list of 100 greatest punchers of all time in 2003.

Both Louis and Schmeling are members of the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Louis–Schmeling paradox [edit]

The rivalry between Louis and Schmeling gave rise to the Louis–Schmeling paradox, a concept in sports economics. It was first identified and named by Walter C. Neale, in his article "The peculiar economics of professional person sports", published in the Quarterly Journal of Economic science in February 1964.[33] The paradox, as identified past Neale, is that the general rule that monopoly is the "ideal market position of a house" does non hold for professional sports.[34] Where non-sporting firms are "amend off the smaller or less important the competition", sporting firms require competitors to be successful: if Joe Louis had had no competitors, he "would have had no ane to fight and therefore no income". Neale resolved the paradox by drawing a stardom between sporting contest and market place competition, holding that "the firm in law, as organized in the sporting world, is not the firm of economic analysis".[35]

The paradox is sometimes re-stated as "commercial sporting organizations need close competition if they are to exist able to maximize their income",[36] as a effect of Neale's further conclusion that "need for competition will decrease if the spectators can predict the outcome of the game". Nevertheless, this has been challenged by Roger G. Noll, who noted in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy in 2003 that "a squad that has dropped out of contentions for a title volition by and large draw poorly, only information technology is likely to sell more tickets if it is playing a squad that is at or near that elevation of the standings than if it is playing some other weak team, even though the result of the latter game is more than uncertain".[37]

Come across too [edit]

- Joe and Max (2002 flick)

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j Dettloff, William. "The Louis-Schmeling Fights: Preluse to War". Retrieved 2009-04-27 .

- ^ "American Experience: John Roxborough and Julian Black". PBS . Retrieved 2009-04-23 .

- ^ Vitale, p. 16.

- ^ "PBS.org: The American Experience". PBS . Retrieved 2009-04-23 .

- ^ Vitale, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d "Volume Review: Beyond Celebrity by David Margolick". Retrieved 2009-05-06 .

- ^ a b Hughes, Langston (2002). Joseph McLaren (ed.). Autobiography: The Nerveless Works of Langston Hughes, Vol. 14. Academy of Missouri Press. p. 307. ISBN978-0-8262-1434-8.

- ^ Schaap, p. 271.

- ^ "The Louis-Schmeling Fights: Prelude to War". Retrieved 2009-04-27 .

- ^ a b c Myler, p. 121.

- ^ a b Schaap, p. 144.

- ^ Deford, Frank (Feb fourteen, 2005). "A Clashing Symbol". CNN . Retrieved 2009-04-27 .

- ^ Deford, Frank (2005). "The Choices of Max Schmeling". NPR.

- ^ Blaine Henry (Feb 27, 2020). "History Lesson: Joe Louis Fighting The Nazis". Fight-Library.com.

- ^ a b Myler, p. 132.

- ^ Erenberg, p. 138.

- ^ a b Erenberg, p. 141.

- ^ Blaine Henry (Feb 27, 2020). "History Lesson: Joe Louis Fighting The Nazis". Fight-Library.com.

- ^ a b Erenberg, p. 142.

- ^ Myler, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Erenberg, p. 143.

- ^ Erenberg, pp. 143-145.

- ^ a b c d due east f Erenberg, p. 145.

- ^ a b Dawson, James P. (June 23, 1938). "LOUIS DEFEATS SCHMELING BY A KNOCKOUT IN FIRST; 80,000 SEE Title BATTLE". New York Times.

- ^ Bak, Richard (1998). Joe Louis: The Great Black Hope. Perseus Publishing. p. 103. ISBN978-0-306-80879-1.

- ^ Bak, Richard (1998). Joe Louis: The Nifty Black Hope. Perseus Publishing. p. 104. ISBN978-0-306-80879-one.

- ^ Mead, Chris (September 23, 1985). "Triumphs and Trials". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008.

- ^ Blaine Henry (February 27, 2020). "History Lesson: Joe Louis Fighting The Nazis". Fight-Library.com.

- ^ John Blossom; Michael Nevin Willard, eds. (2002). Sports Matters: Race, Recreation, and Culture. New York University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN978-0-8147-9882-9.

- ^ "BoxRec: Login".

- ^ Ring of Passion, Internet Film Database, retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ Blaine Henry (February 27, 2020). "History Lesson: Joe Louis Fighting The Nazis". Fight-Library.com.

- ^ Pardalos, Panos K. (2012). "Fantasy League?: Did you Analyze Your Team'southward Network First?". ISE News (University of Florida). Fall 2012: x. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Neale 1964, p. one

- ^ Neale 1964, p. ii

- ^ Arnold, A. J. (2004). "Harnessing the forces of commercialism: the fiscal development of the Football Clan, 1863–1975". Sport in Order. vii (two (Summertime 2004)): 232–248. doi:10.1080/1461098042000222289. S2CID 219693282.

- ^ Vig, Arun (2008). "Efficiency of sports leagues: the economical implications of having two leagues in the Indian cricket market" (PDF). MBA Dissertation: 13.

References [edit]

- Erenberg, Lewis A. (2005). The Greatest Fight of Our Generation: Louis v. Schmeling. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-nineteen-517774-9.

- Margolick, David (2005). Beyond Glory: Joe Louis Vs. Max Schmeling, and a Earth on the Brink. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN978-0-375-72619-iv.

- Myler, Patrick (2005). Ring of Detest: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling: The Fight of the Century. Arcade Publishing. ISBN978-i-55970-789-3.

- Neale, Walter C. (Feb 1964). "The peculiar economics of professional sports: a contribution to the theory of the firm in sporting competition and in market competition". Quarterly Journal of Economics. LXXVIII (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/1880543. JSTOR 1880543.

- Schaap, Jeremy (2005). Cinderella Man. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN978-0-618-55117-0.

- Vitale, Rugio (1991). Joe Louis: Battle Champion. Holloway Firm Publishing Company. ISBN978-0-87067-570-6.

External links [edit]

- Video of 1936 Louis-Schmeling Bout

- Video of 1938 Louis-Schmeling Rematch

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Louis_vs._Max_Schmeling

0 Response to "Americas Hero Again His Victory the Comeback That America Needed"

Post a Comment